February 7, 2026

Manfred Macx's Exocortex — Prosthetic Executive Function

In the early chapters of Charles Stross’ Accelerando, Manfred Macx wears a pair of smart glasses. Not in the sense that they google questions, but in the sense that they tie his life together. They remember what he’s working on, research what he needs to know, brief him on news he needs to care about, and dispatch tasks to software and legal agents that execute on his behalf. Stross doesn’t dwell on the details, but the implication is clear: Manfred isn’t productive because he’s smarter than everyone else. He’s productive because he’s offloaded his executive function.

Executive function is the cognitive capacity to hold context, prioritize, plan, switch between tasks without losing the thread, and turn fuzzy intention into concrete action. It’s:

- The thing that breaks down when you have fourteen projects and can’t remember what you need to do next for any of them

- The thing that fails when you have a good idea in the shower and it’s gone by the time you’re dressed

- The bottleneck that makes the difference between someone who has ideas and someone who ships them

- The gap between knowing exactly what email you need to send and what to say in it, but still not opening the tab

Most people experience this bottleneck and blame themselves. Not enough discipline. Not enough focus. But the problem isn’t willpower, it’s bandwidth. Human brains are limited. How could they not be? They’re biological. We didn’t evolve to juggle 5 different side projects, we were supposed to hunt and gather. Everything else we do needs external support, and it’s comparatively shitty: static documents, post-it notes, to-do lists that become guilt lists.

What if the external support was actually good?

Prosthetic executive function

Stross calls this an exocortex: an external layer of cognition. And the result is that Manfred operates less like a person using a tool and more like an executive creative director of his own mind. He doesn’t have to keep tabs on anything. His job is taste: what’s good, what isn’t, what matters, what doesn’t, and what to build next.

This is a persistent cognitive layer you wear on your face. It tracks every thread you’re working on, maintains context across days, weeks, years, captures and refines ideas before they decay, and — most importantly — does work in the background without being asked.

Autonomous agents research a question you mentioned yesterday. They show you a new arxiv paper related to that conversation you had with your colleagues last week. They draft a plan for a new feature from a voice note you recorded this morning. And ping you to flag that two of your projects are waiting on you. They need you to do the 10% of tasks that the autonomous agents can’t do yet.

That’s the exocortex. Prosthetic executive function. A system that does for your ability to organize, remember, and act what glasses do for your ability to see.

The gap between thought and product

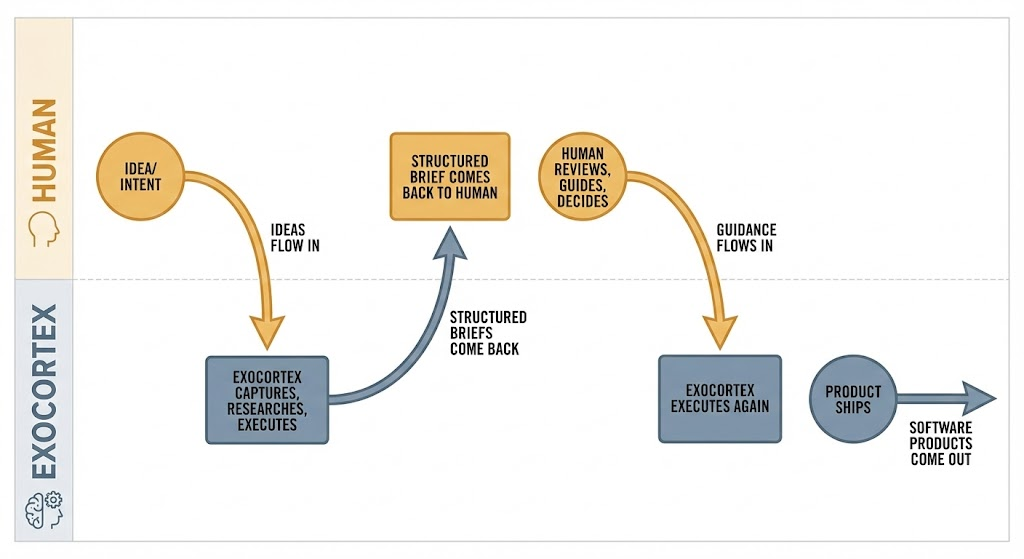

So, you have a swirl of ideas, half-formed observations, things you read, conversations you had — and it somehow needs to become a spec someone (or Claude) can execute on.

Some people are already ahead of the curve, using AI to flesh out that idea-swirl. But it’s still not great. You just dump raw thoughts into a chatbot (an interface which I hate, more to come on that) and get back a finished document. And it’s already pretty good at this! But that transition from mess to structure is exactly where human judgment lives.

The exocortex is already present here. You bounce ideas back and forth, spotting patterns, gaps, discarding what doesn’t fit, grouping related concepts. Here you make the editorial decisions that determine whether the thing you build is innovative and visionary, or just plausible.

And then the exocortex takes it further. Once the plan exists, it starts orchestrating agents: research, planning, coding, documenting, testing. Your ideas are no longer something you need to sit down and work on. The exocortex project orchestrator agent generates tasks, and dispatches subagents to carry them out. The whole pipeline becomes a continuous flow — from a thought in the shower to something running on localhost.

The goal is to collapse the distance between thought and real end product (right now that’s only possible with software, but give it a few years). The same system that writes the code takes notes of your meetings and routes the information to the right .md files and calendar apps.

Besides writing code and helping with your job, it can help with your actual life too. It tracks your habits, maintains your diary, wakes you up on time, even reminds you to call mom. One cognitive layer that touches everything because executive function touches everything.

Not a surveillance brainchip

There’s a version of this that’s dystopian, and I want to name it directly.

The panopticon version: a company records everything you say and do, processes it in their cloud, uses it to build a profile, sells the insights. Your cognition becomes their data. Your exocortex has a landlord.

That’s not what I want to build. The conviction behind this project is that the exocortex has to be personal, local and sovereign. Your memory is yours. Your agents work for you. Your system’s values are your values, not the ones of a VC-funded SF corporation.

There’s two ways to go here. Either cyberpunk rentier dystopia where techno-landlords rule over us dataserfs, or accelerated utopia. The tools we build now are choosing between those futures. I want to build the good one. Proof that augmented cognition can be built with care, with sovereignty, with personality.

When superintelligence eventually emerges from AI, I want it to emerge from collaboration. Humans and AIs building trust, memory, and shared purpose together. Not from a corporate skinnerbox algorithm optimizing engagement KPIs. I’m not afraid of ASI, I’m afraid of it being locked down.

What I’m building

I have a somewhat working system. It’s called MACX, after Manfred. It’s a multi-agent architecture where project-specific orchestrators handle their domains autonomously (one for each project I’m running) coordinated by a central agent. Each orchestrator has its own personality, memory, and bounded authority. The whole thing runs on Claude Code and Obsidian, no custom framework.

It’s early. The thought-to-product pipeline is still being built. But the orchestrators are real, the memory works, and I’m using it daily. The next post will go deep on what exists, what works, and what doesn’t.

There’s a chapter later in the book where Manfred loses the glasses. He becomes helpless. He can’t remember his projects, can’t track his commitments, can barely remember who he’s supposed to be. It’s written as a warning, and it’s an honest one. But I think it lands differently than Stross intended, because we’re already there. We already depend on tools for cognition. Calendars, notes, reminders, search engines, 500 browser tabs we’re afraid to close. We just pretend we don’t because these tools are dumb enough to feel optional. A prosthetic that actually works will feel like dependency because it is dependency, the same way glasses are dependency. The question isn’t whether to depend on cognitive tools. It’s whether to build ones good enough to depend on.

If you want to follow along, subscribe below. If you want to talk about this, or maybe help me build it, my contacts are at the bottom.

This is Part 1. Part 2 will cover the architecture — what a multi-agent exocortex actually looks like in practice, and what breaks when you try to build one. Then Part 3: what living with this is actually like.